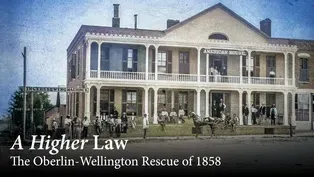

Higher Law: The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue of 1858

Special | 1h 26m 43sVideo has Closed Captions

Discover an amazing story of abolitionism in Ohio and how it impacted the nation.

PBS Western Reserve presents the inspiring rescue story of an enslaved Black man named John Price and the 37 abolitionists from Oberlin, Ohio, whose bravery changed the trajectory of the abolitionist movement in the years leading up to the Civil War. The production is the work of filmmakers Christina Paolucci and Scott Spears of Production Partners Media in Columbus, Ohio.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

PBS Western Reserve Specials is a local public television program presented by WNEO

Higher Law: The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue of 1858

Special | 1h 26m 43sVideo has Closed Captions

PBS Western Reserve presents the inspiring rescue story of an enslaved Black man named John Price and the 37 abolitionists from Oberlin, Ohio, whose bravery changed the trajectory of the abolitionist movement in the years leading up to the Civil War. The production is the work of filmmakers Christina Paolucci and Scott Spears of Production Partners Media in Columbus, Ohio.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch PBS Western Reserve Specials

PBS Western Reserve Specials is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

(gentle instrumental music) (gentle instrumental music continues) (gentle instrumental music continues) (gentle instrumental music continues) (gentle instrumental music continues) (gentle instrumental music continues) (gentle instrumental music continues) (gentle instrumental music fades) (tender instrumental music) (wind whistling) (snow crunching underfoot) - So why would you leave?

Intolerable conditions.

Looking for a better place.

- He was property.

We gotta understand, we're not talking about people in the concepts of human beings.

We're talking about people in the concepts of money and property.

- The story usually goes that he and a cousin Dinah escaped, that they waited for the Ohio River to freeze and crossed when it was frozen.

- All the terrain around on that side that is parallel to Mason County is intimidating.

- This is freezing weather.

I mean, even if you're out in the fields, it's freezing.

- Of course, you would like to stop, but it's like, stop and you die.

So you're talking about running for your life.

I've never had to do that.

- And you don't know who, if anybody, is gonna be decent to you.

- What was that trip like?

What did it sound like?

What did he hear?

What did he see?

You know, the moments of panic.

- So, they had what they referred to as fugitive societies, which in the long and the short of it was the Underground Railroad.

They would hide runaway slaves in churches and homes.

- Then he has to go from place to place where there are very few Black people after you leave Ripley.

And so he had to rely on his own wits, and he had to rely on running into somebody, hopefully, who would treat him decently.

(wind howling) (gentle instrumental music) In Kentucky, you were enslaved and you had no rights.

The person who owned you set the course of your day and of your future.

- The John Bacon Sr. Farm, which, the original farm he bought in 1824 of about 200 and some acres.

And over the years, I don't know how, but he amassed near a 1,000, which was left to his widow, Elizabeth.

He had no river frontage.

All he had was three steep hills.

He had a nice creek going by.

He was building his home, which I think is why he himself did not go after John Price.

And so John was a trusted person.

He was not exceptionally big or brawny.

He must have had a keen sense of where he was and what was across the river.

He had a cousin, Dinah, who lived with him.

When they decided to escape from this farm, it is incredulous to me as to how they got off the farm.

You know, which bank did you try to get down with this high-spirited horse?

Well, once down, though, you only had about 1,000 yards and you were at the Ohio River.

1,000 feet, maybe, and you were at the Ohio River.

But the Ohio River was frozen solid.

Frozen for most of two months.

- That's why I called it the waterways to freedom because all of the outlets were close to where water was.

- As a matter of fact, the largest slave escape in Kentucky involves at least 70 slaves, and they were headed to Ripley.

(gentle instrumental music) - The Rankin is one house that was pretty well known at that time, even, for being a haven that people could find as soon as they crossed the Ohio River.

John and Jean Rankin were well-known abolitionists along with their family.

The Rankin House is still standing and so people can visit to see the landmark and see the stairs leading down to the Ohio River.

And sometimes you hear a story associated with it that you would look across the Ohio River from the South and see a light, and that might guide you to safety.

- [Narrator] Another important abolitionist in Ripley was John P. Parker.

- [Liz] So John Parker was formerly enslaved himself.

He was actually a conductor, meaning that he would physically go into Kentucky and boat people across.

And by doing that, being Black himself, he was risking his life every single time he did that.

- [Narrator] It is not known if the Rankin family or Parker helped Price find his way north because they didn't keep records for fear those ledgers would be stolen and used to track down freedom-seekers.

- Parker estimated he took over 1,000 out of Ripley.

Rankin and his sons, more than 2,000.

- Crossing the Ohio River, passing through Ripley, you had to go inland a little bit more to gain some type of freedom.

- To keep going north, that's a terrible experience in that type of weather.

The best luck they could have had if they were totally doing this on their own, And many, many, many slaves escaped on their own.

It didn't take a white man to help them escape.

- Southern Ohio, you know, we think of Ohio being this state of freedom, but not there.

You know, crossing the Ohio River, you still have a long ways to go.

- If they knew anything at all about the Underground Railroad in Ohio, they knew they needed to get to Red Oak.

Well, that was just full of abolitionists and conductors.

I mean, that was just the place to ride to.

They could have had maybe half an hour, an hour respite there, but it was too dangerous to keep them there.

They definitely would have been moved out during that night.

- So even though we like to have this somewhat glamorous idea of this secret route and that it functioned well, a lot of times you couldn't trust it and you didn't wanna trust it.

It was safer to strike out on your own.

- They would try not to reveal themselves to any white people because they didn't know if they were gonna be helped or if they were gonna be taken back South.

- "Follow the North Star" was a common term used.

So you know that this is, if you're headed that way, you're going in the right direction.

- So I think the route was always shifting because you wanted to be smart about it.

You didn't want slave catchers catching on.

- But you went through at night.

You had to pretty much do it on your own, and you don't know anybody and now you gotta go 10, 15, 20, 30 miles to find somebody who's gonna let you have a sandwich.

(gentle instrumental music) - It would have taken a couple of nights to reach Washington Courthouse, if not three, parts of three nights, considering the weather and the ice.

- You know, it really was a grueling, dangerous thing for them to take flight.

But at the same time, they were taking flight to freedom, and so certainly the stories would pass about how, you know, the system worked, and so if you really wanted your freedom, you were gonna take that chance.

- [Narrator] John Price's daring escape to freedom would pit the people of two small towns against slave catchers, a deeply flawed law, and the federal government.

The events that happened in September, 1858 would have a ripple effect leading up to a bloody Civil War.

- "Think one person can change the world?

So do we."

Well, that's John Jay Shipherd's message.

He was gonna change the world, and he did it by founding Oberlin, the community as well as the college.

- So Oberlin was founded in 1833 as a Christian Perfectionist utopia, or supposed to be a utopia.

- These were communities where a group of people gathered together, typically around some sort of religious covenant to try and live out the gospel or a particular understanding and commit to a particular way of life.

- A place where all individuals could come and worship and be together as one.

- The town takes great pride in being a place where people of color can exist freely.

- I think what makes Oberlin unique was this combination of women's rights, African American rights, and issues of anti-slavery movement, and the fact that many people were drawn to the town because of those commitments.

Many of them were dyed-in-the-wool abolitionists.

- There is, in the Oberlin concept, a notion that we will all become one.

We will become a beloved community.

Race and color will not matter.

But compared to what's going on almost anywhere else in the country, it's extraordinary.

(energetic pensive music) - Clay, forest (laughs) in the middle of the woods in Ohio.

- The soil was bad.

Much of the area was swamp.

It was not going to make good farming land - At that time, Oberlin, Ohio was kind of the western frontier of the United States, the 1830s.

- Well, the Western Reserve in the Firelands was land set aside for soldiers of both the American Revolution and the War of 1812.

- Our founder, John Jay Shipherd, coined the phrase, "Oberlin is peculiar in that which is good."

- 1832, he goes east, trying to sign up potential colonists to settle.

- Arthur and Lewis Tappan were wealthy businessmen from New York City.

They had anti-slavery interests throughout the country.

- So Oberlin was founded as a community in 1833, and the congregation was founded in 1834, basically at the same time.

- From the beginning, the colony was to be a small town with its central activity a school that would be, at the very least, college preparatory.

- Oberlin's transformation from an evangelical Christian community to one that embraced what I call radical racial egalitarianism doesn't happen at the founding.

It happens in 1834 and 1835.

- One teacher, a couple of dozen students.

- In the early days of the Oberlin Colony, my understanding is the town, the church, and the college were all like this.

The church, at times, was extending money to the college to help support the college and various things were going on.

And so it all worked together, and that's why people gathered here.

And the first pastor was John Jay Shipherd, one of the colony's founders.

- [Gary] And then the college is officially launched December 3rd, 1833.

- Oberlin created this environment that religion would play an important role into our community and the development of our community.

(gentle pensive music) - [Narrator] In Cincinnati, students at Lane Seminary led a rebellion.

(tense music) - A group of graduate students, inspired by their most famous, Theodore Dwight Weld, who had been a protege of Charles Grandison Finney.

- He was able to convince the students that they should darn near riot.

You know, we're going to have to be loud about our feelings.

- [Theodore] No condition of birth, no shade of color, no mere misfortune of circumstances can annul that birthright charter which God has bequeathed to every being upon who he has stamped by his own image.

Ought the people of the slave-holding states to abolish slavery immediately!

- And these students promptly began to organize in the Black community, began to preach among their fellow seminarians.

- Those students were threatened with expulsion if they continued to agitate about the abolition of slavery, which was causing the school trustees, many of whom had business relations with slave holders across the river from Cincinnati to get very uncomfortable.

When threatened with, "Either you shut up or you leave," the so-called Lane Rebels decided, well, they would leave under their own, you know, agency rather than stay in an institution that wouldn't allow them to speak on this critical issue.

- In the meantime, Oberlin was about to go under by 1835.

Shipherd, hearing of what was going on down there, decided he would go and try to recruit them knowing that they were being funded by Tappan money.

- The students had some of their own demands to come here, and their demands had to do with, Charles Finney had to become a professor of theology.

- [Liz] But the big decision, the students said, "We're only going to come up if you accept African American students."

- That became a contentious issue for the board and the community and the college to sort out.

- And it came down to a deadlock vote.

So people talk about the importance of their vote.

In Oberlin, it was one vote that made the difference.

- It ended up in a tie vote that was broken by the board chair, Reverend Keep.

And after that, it's history 'cause then Charles Finney comes into the community.

(warm piano music) (warm piano music continues) First Church Oberlin and Charles Grandison Finney were sort of a match made in heaven.

This church was viewed as an outlier.

It's too radical.

It was a place that folks were saying, "Please do not send your sons and daughters to Oberlin College because they are too radical."

Charles Finney was a Presbyterian minister who was not welcome within the Presbyterian Church because his ideas were too radical for different reasons.

So you have a pastor rejected from his denomination and a church pretty much rejected from their denomination coming together and being rebels together.

- And an embrace of not just abolition of slavery as a principle, but the achievement of racial equality.

The town is a real experiment in racial integration well beyond anything that's going on within the college alone.

- [Narrator] Many Blacks, some free, some enslaved, fled the South seeking freedom.

And one destination was Oberlin, Ohio.

- Some passed through on their way to Canada because it is part of a major route on the Underground Railroad, but a large number stay and they build family networks.

So, families where one member comes in the 1840s, other family members may come 10 years later.

- So we have southern migrations coming in.

Later on they came in for a different reason, but coming to Oberlin, of course, they're looking for freedom, right?

So they're trying to look for that area that is welcoming to them.

- Well, there are about 500 people of color living in Oberlin and surrounding Russia Township.

People of color made up about 20% of the population.

- They were really setting the tone for how Oberlin, how strongly anti-slavery and abolitionist the town should be, always pushing their white fellow community members like, "This is good, but we should be doing more.

We can do more."

- [Narrator] The Fugitive Slave Act was passed as part of the Compromise of 1850, requiring that slaves be returned to their owners, even if they were in a free state.

The law failed to settle tensions between the North and the South.

The issue of slavery continued to divide the nation for the next decade.

- First Fugitive Slave Act was signed by George Washington, but it was sort of nebulous and it wasn't clear what the procedures were for seizing and bringing fugitives back.

And many of the Northern states resisted it.

They passed their own local laws, provided for jury trials or other means of making it difficult, in some cases impossible, for enslavers to bring people back into the South.

- Not just back to slavery, but sometimes just to slavery because it's very hard for any free Black to document that they are free.

- And as part of the Compromise of 1850, the Southern states insisted on a reinforced or stronger Fugitive Slave Law.

That's the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

And Congress passed that law.

President Fillmore signed it.

And that really reinvigorated the whole process of slave hunters going back and forth across the Northern states and tracking people down and using legal means to drag them back into enslavement.

So the period from 1850, really into 1861, was characterized by tremendous struggles over enslavement on one hand and rescue on the other because the Fugitive Slave Act was like a dagger of bringing slavery into Northern states that had abolished it.

And suddenly people in the North who might have been ambivalent about slavery, might have been willing to tolerate it as long as they didn't have to see it, suddenly they were seeing their fellow townspeople seized and dragged in chains.

- Because when we think of slavery, we just think of a Southern issue.

But this Fugitive Slave Act brought this attention throughout the entire nation where it's a constitutional issue now where we are having debates over, what's a slave state?

What's not a slave state?

Who's a slave and who's not a slave?

Dred Scott, prime example as well.

You know the Dred Scott Case.

Is Dred Scott a slave?

Is he not a slave?

Are we using the Fugitive Slave Act?

- In 1857, Chief Justice Taney of the US Supreme Court says in the Dred Scott Case, "Black people have no rights that white people are bound to respect."

He makes it clear that he does not believe in Black citizenship.

If you are not a citizen, then what are you, right?

If you are a free Black person, - The Fugitive Slave Law run havoc on free Black people, you know, in the North because they were no longer being protected even by state laws.

- And so a movement emerged among Black and white people in the North either to defend the captured fugitives in court, so-called fugitives, in court or more actively, actually, to interfere, to wrest them out of the control of the enslavers, and in many cases, to help them find freedom in Canada.

And Oberlin was a real hotspot of this movement.

You know, they had bragged, the Oberliners had bragged that no fugitive had ever been taken.

- And for Northerners, it kind of woke them up a little bit because prior to that, they could kind of ignore slavery as something that happened down there.

But suddenly in the Fugitive Slave Act, they could be called upon to help slave catchers.

And if they didn't, they could get into trouble.

Or maybe they had been just fine with people escaping, maybe giving them food or shelter, but now they could see more serious consequences.

- Oberlin, from very early on, is perceived as a sanctuary city, in the lingo of today.

And it takes pride in that role.

The Fugitive Slave Act is passed, and the town meets to denounce it and to try to figure out how it should respond.

And it's not only to the Fugitive Slave Act, but it is particularly to the Fugitive Slave Act because essentially what the Fugitive Slave Act is saying is, "What you've been doing in Oberlin is illegal now under federal law."

There's a three-day town meeting on, what do we do?

And people pledge that they will, that Oberlin will be a safe haven.

It will be a sanctuary.

On the other hand, as early as the late 1840s, there's a public gathering of African American Oberlinians that says, "Be careful of man-stealers.

Be careful of slave hunters."

- Private law enforcement was pretty common in the 1850s.

There were no police forces.

There were no real formal means of enforcing the law.

And so it was pretty common for private individuals, right, to be either deputized or enrolled for the purpose of law enforcement.

The Fugitive Slave Act specifically allowed private individuals, as long as they had a documented power of attorney.

- And when people decided to escape, the slave catchers were deputized, in many cases, in order to go and find and catch slaves.

And then there were these, what we call modern bounty hunters who were paid to go and came with the authority of the law.

They could come into a city and say to the marshal or the sheriff, "I am here to bring back this property, and I need your help to get that person so I can bring them back to their rightful owners."

And police or sheriffs, in many ways, colluded with, participated with those folks trying to re-encapture Black people.

- In the 19th century, federal marshals were not paid.

The federal marshal for the district and the deputies worked on commission, and they were paid by the job.

Anson Dayton had originally been a Republican, and he had been the town clerk of Oberlin.

And then in a really stunning move, the City Council of Oberlin dismissed Dayton and they appointed John Mercer Langston.

John Mercer Langston was the first Black public official in the United States.

Dayton, furious about this, furious about this, and he changed his party from Republican to Democrat.

He sought appointment as a Deputy United States Marshal, and of course he found a soulmate in Matthew Johnson and became Johnson's assistant in Oberlin.

Really, you could call him Deputy Marshal for the purpose of dragging people back into slavery.

- And so marshals was hanging around Oberlin being very concerned and making sure that if anything happens, they are there to make sure that the Fugitive Slave Act will be enforced.

- I think in the country that is even invading Northern Ohio, that really Black folk aren't secure anywhere.

- I mean, you can't...

The fever that was out here, oh, we should be feeling it now.

The fever that this country is feeling now, what do you think the fever was like then?

- Country is at high alert.

Something is happening here, and it doesn't feel good.

Something is soon to break.

(tense dramatic music) And I think that tension was a national tension.

It wasn't just a tension in the Cleveland Federal Court.

It's in the country.

- And Oberlin in particular stood out because of the multiracial solidarity that it showed, that white Oberliners and Black Oberliners were united in their opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

- [Narrator] Slave catchers appear in the Oberlin area, putting the community on notice.

- I found Oberlin surrounded and filled with alarming rumors to the fact that slave catchers, kidnappers, Negro-stealers, they were lying, hidden, waiting just for the opportunity to put their bloody hands on some poor creature and drag them back into lifelong *******.

- Federal marshals were like deputized bounty hunters.

Not very well thought of around here.

In fact, they had to be rather careful.

- Why do we have federal agents hanging around Oberlin, right?

It just created a atmosphere of contention.

- So a lot of cities, bigger cities and Oberlin had what were called vigilance committees to carefully watch any strangers coming into town and patrol and keep an eye on places where they knew freedom seekers were staying to make sure that they were safe.

- There were three attempted captures right on the eve of this.

There's the Democratic Marshal Anson Dayton the bad guy in the story.

Anson Dayton is kind of ready to go out and do the Democratic dirty work of recapturing slaves so you have a villain here.

- We're gonna unite as a group, right?

We're gonna come together and we're going to unite.

And we are going to say that whoever comes to Oberlin will be safe.

We will protect them, we will harbor them.

We will make sure that they gain the equality that they deserve.

- What's remarkable about the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue is the way in which you do see this mobilization of a wide cross section of the communities.

And what's also remarkable is the way in which you see Black and white people working together.

(soft instrumental music) - There was a Kentucky slave catcher named Anderson Jennings who came to Oberlin in pursuit of a fugitive.

Couldn't find him, but he happened to observe John Price and believed that he recognized him as a fugitive from the Bacon Farm in Kentucky from his neighbor.

- The owner, Bacon, gave him kind of the legal authority to do this.

- So he assembled a small posse, and they went to Oberlin for the purpose of capturing John Price.

- A lot of this was hatched at what was called Wack's Tavern here in town.

He was going to allow them to hatch this plan.

- If they were to capture John Price in the public, then there would be a uproar.

And the marshals knew that if they got John Price from working from the square itself, then the citizens of Oberlin would have protected John Price so they had to get him out of the public eye.

- They paid a young boy, Shakespeare Boynton, from a Democratic family to lure John Price out of town saying that there was work.

And they have weapons and they demand John drop his like, penknife and go with them.

And John is clearly outnumbered so he goes with them.

And they kind of circle around Oberlin on the east side of town to Wellington.

And they're going to Wellington because that's where the southbound train, they can meet up with that and, you know, have a clear coast down to at least Columbus, if not Kentucky.

- [Narrator] The slave catchers' plan falls apart and will lead to a confrontation.

- I supposed to do what I could to secure, at least, this form of justice for my brother whose liberty was in peril.

(somber dramatic music) - So they're in a wagon.

They're taking this guy towards Wellington.

They're riding by a farm.

You couldn't have gone by unnoticed 'cause how much traffic did you have in 1857?

If you had three or four wagons a day, you'd look up and wave and it'd be your neighbor.

This is somebody going by you didn't know at a pretty good clip.

So yeah, it might have been, "Hmm, that looks suspicious.

Wonder what's going on."

- They pass two other people in another wagon.

One is a tin peddler and one is a student of Oberlin College, an anti-slavery student.

And they don't do anything at the time, but they know.

They see who's in this wagon and know that's not the right mix of people.

- Suddenly, news reaches town in the early afternoon.

- People of Oberlin was very upset with the capturing of John Price and decided to do something about it.

- There's definitely a sense, this is our moment to finally enact our principles, to do this physical confrontation.

- Like John Watson, a Black grocery store owner.

He immediately sets off to Wellington with another Black man and they go to the town hall to try and, I believe, form a warrant against the kidnappers.

Anything to stall what is happening.

Meanwhile, in Oberlin here, a lot of people start gathering in the square, what today is called Tappan Square.

You had students and residents, men and women.

Women typically didn't go to Wellington that day, but a few did.

And there's a great story of a man jumping up into a wagon and kind of waving his hat and raising guns and saying, "I'm gonna rescue John Price."

And the crowd just gives this massive cheer.

- [Narrator] The Oberlin Rescuers would head eight miles south to Wellington in an attempt to save John Price.

- 1824, I believe, is when Wellington became a village.

- People from the big cities wanted a place that they could come to for their summers and where they could be summer in the country.

Well, Wellington happened to be the country area at that time.

We have rolling lands, lot of dairy farms, very pastoral scenes.

- It was really bustling.

Dr. John did a very, very smart thing by making this a 15-minute stop because people got out, they looked around, decided, might be a good place to put a business.

- [Janet] And at one time, Wellington was the biggest cheese exporter in all of the United States.

- I'd say the three things that we're the proudest of is, we're proud of the Spirit of '76.

We're very proud of the slave rescue.

And Myron T. Herrick, who was the most popular ambassador to France since Benjamin Franklin.

- [Narrator] Hundreds would gather outside the American Hotel while tensions grew inside.

- When it originally hit the papers, it was referred to as the Wellington Slave Rescue.

And that's always fun 'cause when the book come out, it was the Oberlin-Wellington Slave Rescue, and anybody that had grandparents kinda huffed at that, going, "Where are they getting off calling that Oberlin-Wellington Slave Rescue."

(gentle instrumental music) - And Wellington was already kind of hopping that day because there had been a fire earlier so people, you know, come out to look at the fire.

And so there was already a pretty big crowd.

- Well, you were in town for the fire, and slavery was a hot-button issue.

Might as well stay for that too.

- They surround the hotel in Wellington, which is where Herrick Library now stands so the hotel is gone.

And everything kind of pauses at the hotel.

Again, they're trying to figure out if John is fugitive.

And eventually John even admits he had escaped and maybe he has to go back to Kentucky.

- And the slave hunters brought him out onto a balcony to speak to the crowd, obviously under extreme duress and they probably had a gun in his ribs.

And he told the crowd, "They've got the papers for me, so I suppose I have to go back."

But you know, you can't hardly credit that as the way he really felt because there were four Kentuckians surrounding him at the time.

- But regardless of whether he wanted to go back to Kentucky or not, he wasn't going back to Kentucky.

They decided, he was gonna be free if he wanted to be free or if he didn't want to be free.

They were not, you know, giving in to any deputized bounty hunters taking anybody.

- And then they take a look at the paperwork that the slave catchers have and the marshal and yeah, it looks right.

They missed that train, the five o'clock, and the Sun starts going down.

And eventually the crowd just starts saying, "You can't have him."

- I think the crowd was mixed all the way around.

But the two, the active groups of young men who were the ones who were going to aggressively confront the slave owners met in two groups.

- They start breaking into the hotel, and there was people breaking into the front door.

A lot of college students at the front door.

At the back door are a lot of Oberlin African American businessmen like John Scott, a saddle maker, and the Evans brothers, Wilson Bruce Evans and Henry Evans, Jerry Fox, who's a fugitive himself.

- Oberlin students, mostly white in the front of the hotel.

And John Copeland and his mother, Black men at the back because there were two staircases.

- You had this whole mix of people, and once they're inside, it's like a brawl and you have some punching and tackling and hair pulling.

Eventually, they make their way up to the attic or the second floor where John Price is being held.

And some people who had already been inside negotiating, when this all breaks out, they managed to huddle around John Price.

- The two groups of young men burst through the door, knocked the enslavers to the ground, took ahold of John Price, and really sort of like a mosh pit, you know, just carried them on their shoulders down the stairs to a wagon that was waiting, and that was being driven by Simeon Bushnell.

- They kinda get into the wagon and Simeon Bushnell grabs the reins and they go racing back to Oberlin.

(intense dramatic music) To follow John's story, he's going to hide in the home of a man named James Fitch, a white man.

Fitch is a well-known abolitionist.

Even though their house is one of those that's known to have secret hiding places, he's only there for a little bit of time because they realize that's a bad place to stay because everyone knows Fitch is involved.

The house is gonna be watched.

But Monroe and Fitch go to James Fairchild and ask if he and his wife will shelter John Price.

- Who was a faculty member at the time.

I always like to call him the behind-the-scenes guy.

He was known to be an abolitionist, but maybe not quite as active as others, but he was willing to have Price in his home for a few days.

- Which was smart because nobody did suspect them.

Nobody watched their house.

So John stayed there.

Things were quiet for a couple days.

He's escorted up to Canada by John Copeland.

- We have multiple recollections of what happened in Oberlin.

There are newspaper stories, there are memoirs.

You know, there are letters, there are recollections from the time, people talking about what their experience was.

There is not a single sentence about how John Price felt about it.

That even the abolitionists who had secured his freedom did not think to talk to him about what this experience had meant to him.

You know, he had been living a peaceful life as a farm laborer, and suddenly, you know, in the space of a day he was kidnapped and then freed and then hidden and then a few days later, taken to Canada.

And you have to wonder, what was his reaction to all of these events?

But nobody wrote it down.

- His story, the ending of his story is yet to be written.

We don't know.

We lose this young man, this young teenage man.

We lose him.

He could not have kept the name of John Price, not with all of this political heat and this huge trial looming over his head and him still being a fugitive.

So he too would have had to take on a name such as Harriet Tubman did and Frederick Douglass and people like Robert Smalls.

I don't know if Robert Smalls changed his name, but I mentioned the three of them collectively because these are fugitive slaves where, once they got to freedom, we know, we were able to follow them.

We know the rest of their story and a lot of the great things that they did.

John Price, his story is yet to be finished.

(gentle instrumental music) - [Narrator] The rescuers were proud of freeing John Price, but an unjust law would bring the full weight of the federal government down upon them.

(tense pensive music) - Federal court handed down 37 indictments for involvement in the rescue of John Price.

The indictments were 25 people from Oberlin, including 12 Black men.

- The Black rescuers, these are not marginal people.

These are very important members of the community who, like the folks from the college and from the community, are willing to stand up and say, "These are our principles."

- And then another 12 people from Wellington who had assisted or were said to have assisted in the rescue.

John Price was one of the people indicted, but he was never arrested.

They couldn't find him.

There was a second indictment of three others.

Henry Peck, Ralph Plumb, and James Fitch, who were leaders of the Oberlin community, but who had not gone to Wellington.

And they were indicted for conspiracy.

- [Narrator] The African American rescuers were prominent members of the community who put their lives on the line to assist those fleeing slavery.

- John Watson's grocery might have been a place that you would pick up things to eat and to cook at home.

You knew him on a day-to-day basis.

You might go to John Scott's saddlery because after all, you needed new harnesses for your horses.

You might go to the carpentry shop run by Wilson Bruce Evans and his brother Henry in order to have a coffin made.

These are people who were thoroughly integrated into the trade of the town.

So you knew them as your neighbors.

There was much less residential segregation.

You knew them as people who went to church with you.

You knew them as people who were part of your day-to-day, passing them on the street.

- [Narrator] Pro-slavery law enforcement would do anything they could to bring down the rescuers.

- Marshal Johnson was a conniver and a deceiver.

He had come to Oberlin under the false pretense that he had no intention of arresting anybody.

And that's actually how he gathered the names of the people who were involved in the rescue.

And then he reported back to George Belden, who was the United States Attorney for the Northern District of Ohio.

And that's how the indictments came to be.

In the 1850s, there was no random selection of jurors.

Grand jurors and trial court jurors were handpicked by the marshal.

Matthew Johnson brought in a panel of 40 people, all of them pro-slavery Democrats, and then 12 were selected to be on the jury.

The defense was allowed challenges, but didn't make any difference because if you removed one pro-slavery Democrat, you just got another one.

Yeah, Lewis Boynton, who had helped in the kidnapping, was one of the grand jurors.

- So there was already some shady political goings-on.

And that was, again, because the government was trying to crack down on Oberlin and enforce the Fugitive Slave Law.

- The President at that time, he was, Buchanan, was very, very upset.

And he decided he was going to take and make a point of prosecuting Oberlin for its abolitionist activity.

And this was his chance to do that.

And so he decided he was gonna prosecute them to the fullest extent of the law at that time.

- [Narrator] Despite the seriousness of the charges against them, they celebrated their defiance of the unjust law.

(light instrumental music) (light instrumental music continues) - The Felons' Feast happened in between the indictments and when the trials actually began.

The Felons' Feast was in January, and I believe the trials began around March of that year of 1859.

- I gotta say, why were they called the felons?

Why did they do the Feast of the Felons?

They celebrated their criminality, okay?

For the ideology.

- And they give many speeches about how wrong slavery is.

This is an opportunity to reaffirm why they're doing this and why they think it's right.

And they think it's patriotic what they're doing, defying the law to try and end slavery.

- Bottom line is that it was bigger than John Price.

- This was the very first time that civil disobedience or higher law was considered for any purpose whatsoever in a US court.

And the higher law, of course, was that slavery was antithetical, was opposed to the whole concept of human freedom under God.

- They took tremendous risks to do this, and many of them paid the price because the president at the time, James Buchanan, was none too pleased with what was going on in Oberlin because this was going to create trouble across the country.

So the punishment for the rescuers, when they rounded people up, was not just the people that were directly involved that day, but practically every prominent Oberlin citizen they could get their hands on as a way of setting an example for the rest of the country.

Meanwhile, Oberlin was trying to set its own example, right?

Of, this is what it means to live the life of faith and to take it seriously.

- [Narrator] The rescuers were set to be tried in the federal court in Cleveland in the spring of 1859.

- In the 1850s, there was no random selection of jurors.

Grand jurors and trial court jurors were handpicked by the marshal.

He assembled both of the juries that would try the two cases of Bushnell and Langston, again making sure that there were no Republicans.

Cleveland and the Northern District of Ohio, it was one of the most anti-slavery locales in the entire United States.

And yet we ended up with juries with no anti-slavery people.

(somber pensive music) - [Narrator] The trial began with little hope that the rescuers would be acquitted.

- The 31 or so who were actually arrested, they were eventually committed to the Cuyahoga County Jail because there was no federal jail in Cleveland at the time.

Well, the sheriff, whose name was Wightman, was an abolitionist Republican.

Remember, this is Cleveland, and the local officials are all abolitionist Republicans.

So he told the defendants that he welcomed them as guests, not prisoners.

And they published a newspaper from jail.

In 1850, the process was to try the defendants one at a time.

There were 37 of them.

There were going to be 37 trials.

Well, trials were much shorter then, a couple of days, but even so, you know, 37 people, it was going to take a long time.

The first person brought to trial was an Oberlin bookstore clerk named Simeon Bushnell.

And he, as you might remember, he was the wagon driver.

He was the person who actually brought John Price from Wellington back to Oberlin.

- [Narrator] Albert G. Riddle was the lead attorney for the rescuers.

He was a dedicated abolitionist who later served in Congress.

He made speeches in favor of arming slaves during the Civil War.

- There were probably about 25 or 28 defendants in the courtroom so they're taking up the front rows, and then there are spectators.

Spectators are all from Cleveland.

And when Riddle says, "I am a votary of the higher law," I don't know that people were cheering, but they were on the edge of their seats and all in favor, right, in the spectators' section, there was tremendous support for that defense.

Now, the prosecutor, name was George Belden, had spent his argument ridiculing Oberlin, the saints of Oberlin, the do-gooders of Oberlin.

They think that the law's just a joke.

They think they can violate the law.

And he was putting Oberlin on trial as much as Bushnell.

And his whole argument was based on repudiating the idea that there could be a community dedicated to abolitionism.

And then Riddle gets up and he says, "That's right."

He says, "That's right.

We are adherent to that higher law.

We do believe in the higher law.

We do believe in the Declaration of Independence.

We do believe that all men are created equal, and we don't concede that anyone could be enslaved, including John Price."

(stirring instrumental music) I don't know that they applauded, but their hearts and their reaction was totally on Riddle's side.

- [Narrator] One tactic used by the defense was to challenge which court had authority over the case.

- That happened all the way through, whether the authority of the federal court or the authority of the local state courts was going to be followed.

We're gonna see that again.

The higher law defense was unknown before the trials of Simeon Bushnell and Charles Langston.

In earlier cases, the defense strategy had often been to attack the documents that were being used to support the prosecution.

And in the 19th century, there was a much greater emphasis on technical details.

You know, you think today about, oh, you know, released on a technicality, but that's nothing compared to what they were doing in the 19th century.

The wrong form, the case was over.

And these were all fine technicalities, small technicalities that the defense raised, hoping that one of them might stick.

The jury was instructed by Judge Hiram Willson basically to convict.

The jury instructions in those days allowed the judge to express an opinion about guilt or innocence.

And here Judge Willson, also a Democrat, also a Buchanan appointee, basically told the jury, "Just go ahead and convict."

But they stayed out for three hours.

They deliberated for three hours.

That was unusually long in that era, and especially long given the judge's instruction that the defendant ought to be convicted.

But they came back in three hours with a conviction.

- I think in some ways, Oberlin was surprised.

They thought they were following the higher law and that people agreed with them, and I think most Northerners did.

But still, it was maybe a little bit of shock, like, "Oh, he was found guilty and..." But he clearly was breaking the Fugitive Slave Law.

So he was tried and sentenced to a fine and a period of time in prison.

And then one of the big shocks was that they were just gonna roll over right quickly and try Charles Langston using the same jury.

And that, everyone kinda threw up their arms.

Even legal experts saying like, "You can't do that.

You can't just reuse the same jury for somebody else's trial."

- And at that point, the defense lawyers and the defendants say, "Well, we're not gonna cooperate with that.

You know, we're not gonna cooperate."

And so the judge ordered them to jail, and they stayed in jail, you know, till May.

- [Narrator] Straight out of a modern-day legal drama, a technicality would swing the trial in a new direction.

(soft instrumental music) - The Lorain County Sheriff walks into the courtroom, announces that he has indictments and he's going to arrest the four prosecution witnesses.

The federal marshal says, "No, I have writs of habeas corpus releasing them from your state court custody."

Right, and so they're in a federal court.

Obviously, the federal court order is going to dominate, right?

And for the time being, the witnesses stayed free.

But there was more to the story.

Something else was going to happen.

- The slave catchers got their kind of authority through Columbus.

They got the marshal and deputy from Columbus.

They should have gone to Cleveland.

And according to the Fugitive Slave Law, you're supposed to do it in the proper jurisdiction.

So they were filing kidnapping charges against the slave catchers based on that.

- The Ohio Supreme Court denied the writ of habeas corpus in May.

The four witnesses were headed back to Cleveland to testify, and they were intercepted in Lorain County and arrested.

So, and their trial was scheduled to take place three days before the remaining federal Fugitive Slave Act cases.

- So it's all coming to head at the same time.

The slave catchers think they are going to be found guilty of breaking this law, and they would have to spend time in prison.

- Of course, the witnesses were furious and desperate to get out of the Lorain County Jail.

And so the Lorain County prosecutor and the federal prosecutor made a deal that all of the charges against everybody would be dismissed.

And the judge sentenced Simeon Bushnell to two months in prison and a $600 fine.

That doesn't sound like much, but $600 was actually probably a year's income for a bookstore clerk.

It was a crushing, crushing sentence.

But of about 200 known proceedings, fewer than a quarter of them resulted in freedom for the captive.

And the overwhelming majority were resolved in favor of the alleged slave owners.

- [Narrator] During sentencing, one man's eloquence would challenge the court's moral authority to judge a man based upon the color of his skin.

- So Langston had to sit quietly through his own trial, watch the conviction happen, but then he was allowed to speak at sentencing.

- I am, for the first time in my life, before a court of justice charged with the violation of the law, and now I'm about to be sentenced.

- Charles Langston's speech, which he wrote in jail and delivered in the courtroom, is really a masterpiece of rhetoric citing again claims of the justice of the Declaration of Independence and the War for Independence as a part of the rationale for the emancipation of people of color in the United States for the end of slavery.

- That the fundamental doctrine of this government was that men, all men had a right to life and liberty.

- He said, "I come before you an outlaw of America, a person whom the Supreme Court says has no rights."

And he says, "I did not get a fair trial."

- And I have had no such trial!

- And then he said, "I salute, you know, I honor the people who through their own power have freed themselves from slavery."

- Outrunning bloodhounds and horses, swimming rivers and fording swamps, and reaching at last, through incredible difficulties what they, in their delusion, suppose to be free soil.

- And he said, "If I ever have another chance to defend a fugitive, I'll do that, and we will fall back on the rights that God gave us."

Again, he's invoking the higher law.

He's defying the court.

- We as a people have consented for 200 years to be slaves to the whites.

We have been scourged, crushed, cruelly oppressed, and have submitted to it all.

- I mean, I think that that is the most important thing about, for me, in that whole trial process was for Langston to be able to make a clear statement and defense of his actions and actions of his fellows.

- Being identified with that man by color, by race, by manhood, by sympathies such as God has implanted into us all, I felt it my duty to do what I could towards liberating him.

- He was trying to convince the kidnappers that they were never going to get John Price back to Kentucky, and they should simply agree to release him.

And Langston participated in a lengthy series of negotiations, mostly with Jennings, who was the leader of the kidnappers, trying to persuade them to resolve everything peacefully by releasing John Price.

- If ever again a man is seized near me and is about to be carried southward as a slave before any legal investigation has been had, I shall hold it to be my duty as I did that day to secure for him, if possible, a legal inquiry into the character of that claim by which he is being held.

- Charles is saying, "Now look, I'll do the time because I'm gonna stand for the higher law because the Supreme Court, the federal courts, the local jurisdictions, they're all voting against me.

And I would rather stand and be free with God in jail than to bow down and accept what you all are trying to put in front of our face."

- What Langston had done was attempt to resolve things peacefully.

So there was one crucial item of evidence against Langston.

Both Jennings and one of the other slave catchers, Lowe, testified that during the negotiation, Langston said, "It's no use resisting, we will have him anyhow."

And they repeated that sentence multiple times.

Langston, "We will have him anyhow."

And the crucial pronoun was we.

If Langston had said, "They will have him anyhow, let's resolve this," he would have been innocent.

If he said, "We will have him anyhow," well, that's a threat, right?

Which would have made him guilty.

- I do know him as a man, as a brother who had a right to his liberty under the laws of God, under the laws of nature, and under the Declaration of American Independence.

- Charles Langston was among the very first students of color to attend Oberlin College.

His father was a slave holder.

His mother was his emancipated slave consort.

And Langston, Charles Langston, with his older brother, Gideon, came to Oberlin in 1835 when his younger brother, John, was still much too young to come.

- And so it's very important that these are mixed race individuals raised initially to become gentlemen in the Virginia model.

But when their father dies, as mixed race Virginians, they can't stay and pursue that.

So that's when they go to Chillicothe.

The two older ones are the first two students at the Oberlin Institute of color.

The youngest one, John Mercer Langston, will become the most famous of all Oberlin graduates of the 19th century and a leader of African Americans to the end of the century.

- He was the first African American elected to a public office.

- Oberlin becomes this interesting, important chapter in their lives that educate them, that nurture them, that they find their voice.

- I was seen as an outlaw of the United States.

The Fugitive Slave Law under which I am arraigned is an unjust one, one made to crush the colored man and one that outrages every feeling of humanity as well as every rule of right.

- Langston could put in the public record his own agency, his own voice to speak on behalf of the oppressed and to put on public record that they could never get a fair shake in this country as it is presently configured.

"I am standing on the right side of God, even as I know that everybody in this courtroom are going to rule against me.

But I can stand here knowing I will take the punishment because I know that my stance is right, and I'll take whatever punishment is given me."

- If ever again a man is seized near me and is about to be carried southward as a slave before any legal investigation has been had, I shall hold it to be my duty, as I held it that day, to secure for him, if possible, a legal inquiry into the character of the claim for which he is being held.

- But he's basically trying to get these white judges and jurors to understand, if you were in my situation, you would have done exactly the same thing.

- I ask you, Your Honor, while I say this, to place yourself in my situation.

That if it was your brother, if it was your friends, if it was your wife or children, then not only would you demand the protection of the law, but you would even invite your neighbors.

You would ask your friends.

You would ask all of them to say with you that these, your friends, just like John Price, they could not be taken back into slavery.

And no matter what the laws might be, you would honor yourself for doing it, your family, your children, to all generations.

They would honor you for doing it.

And every good and honest man would say that you have done right.

(stirring dramatic music) - Again, they cheered his speech.

The spectators were on his side.

And then it was the time for sentencing.

When he turned to Langston, the judge said, "You do me a disservice, Mr. Langston.

I understand why, as a Black man, you would react the way you did to the fugitive slave capture.

And I believe, therefore, that your sentence should be much lower."

- [Narrator] Langston's speech so moved the judge that he reduced the sentence to 20 days in the Cuyahoga County Jail and fined $100.

- So after about 80 days in jail, everyone is released.

Simeon Bushnell has to spend a few more days in jail because technically his prison sentence lasted a little bit longer.

But the majority of men are released and Oberlin has a grand celebration in First Church.

Lots of speeches and celebrations and women throwing flowers down on people.

They are released in July of 1859.

- [Narrator] After the trial, two of the rescuers would join a daring raid into the South.

Following their principles, they were willing to risk their lives to end slavery.

- John Anthony Copeland, who was a young Black man, grew up in Oberlin and gave his life in resistance to slavery.

He and his relative, Lewis Sheridan Leary were the only two of the people involved in the Oberlin Rescue who went on to Harpers Ferry.

Copeland was the person who escorted John Price to true freedom, to permanent freedom across Lake Erie and into Canada.

- [Narrator] By the time someone would reach Lake Erie, they could be in Canada within about a day's sail.

- Oberlin actually had an outpost in Chatham specifically for the purpose of educating and helping fugitives, so that was clearly the most likely destination.

John Copeland was born to free parents in North Carolina in the 1830s.

His family was reasonably prosperous for free Black people in North Carolina.

But it was a tenuous existence because there was always the threat of enslavement.

You know, you had to carry papers, you had to be in after dark, you couldn't own certain kinds of property.

The Copelands decided to leave and travel to the North to free territory.

And there were really, you know, three ways that Black people resisted slavery.

One was simply by fleeing, you know, by leaving, by getting away, by making their escapes, by fleeing to freedom.

The second was freeing fugitives, defending fugitives in the North and interfering with the attempts to recapture them.

And the third one, of course, was violence, was actually armed resistance to slavery.

And John Anthony Copeland did all three.

And then as a young man, he was involved in violent intervention on behalf of fugitives.

He and a friend actually used hickory canes to beat a US Marshal, who was known to be involved in assisting slave hunters.

During the Oberlin Rescue itself, Copeland threatened the slave hunters with a gun, frightened them to go back up into the hotel.

Copeland was one of the first two people to crash through the door and rush John Price into freedom.

- He could not live with the idea that one human being could enslave and oppress another human being.

And for that he would be willing to give up his life.

- Well, John Brown had been in Chatham in May of 1858, the same year, for what he called a "good abolitionist convention."

It was the first time that he announced to anybody his plan to go into the South and free slaves.

John Brown is in Cleveland just before the trial started, but this is all big news, right?

The Oberlin Rescue was a big story in Cleveland at the time.

The national newspapers were there.

And to Brown, this was a momentous event because it involved the alliance of Black and white people on behalf of the freedom of enslaved people.

And of course, that was his whole plan, to assemble a multiracial army that would invade the South and free the enslaved peoples.

But John Brown had been so impressed by Charles Langston's speech and the militancy of the Oberlin Rescuers that he sent his son, John Brown Jr. to Oberlin to recruit soldiers for his invasion of Virginia.

And Brown Jr. first sought out John Mercer Langston.

John Mercer Langston called his brother, Charles Langston.

Charles said, "I will find you the two bravest men I know."

And he introduced Brown Jr. to Copeland and Leary.

- By the time John Brown comes around recruiting, you know, he's probably grappling in his own mind, you know, "How do we end this thing?

How do we stop this cruelty?

How do we bring about justice in this situation?

And it doesn't look like the courts are going to give us any leeway.

The Congress is passing more and more laws that continue to re-enslave us and to solidify the system of slavery."

- Lewis Sheridan Leary was born free also in North Carolina, and he also fled the slave states and came to Oberlin.

Was roughly the same age as Copeland.

Leary was said to be more hotheaded.

Copeland was more intellectual, but the two men grew up together.

They were friends, they were colleagues.

Copeland and Leary believed that they were going to engage in a lightning raid to rescue slaves the same way Brown had done in Missouri and bring them back into free territory.

Of course, that was not Brown's plan at all.

Brown had plotted a much more extensive invasion in which he would capture territory and use it as a base of operations to spread out across Virginia and make multiple attacks.

But Copeland and Leary had no idea about that.

They arrived at Brown's headquarters in Virginia on a Thursday, and the raid itself began on Sunday.

They hardly had time to get to know John Brown.

As you might know, Brown had commissioned several hundred pikes that he wanted to use to arm the enslaved people whom he thought would come and join him.

There were five African Americans.

Two died in the raid.

One escaped and two were captured.

- As a military exercise, it's a failure.

Lewis Sheridan Leary dies during the attack.

- And after Leary was killed in the rescue, many years later, Charles Langston married Leary's widow and of course they had a daughter and the daughter had a son, and that was the poet Langston Hughes.

While Copeland was in jail in Virginia, the despicable Marshal Matthew Johnson from Cleveland traveled there in the attempt to inveigle a confession from Copeland that he could use against the people of Oberlin.

That he saw this as an opportunity to obtain evidence that would allow him to go back and re-indict the people who had recently made the agreement that led to the dismissal of the charges.

And Johnson fed him lie after lie about the involvement of the Oberlin people in the John Brown Raid, none of which was true.

- Copeland's letters home are among, I think, the most moving letters written by any African American on the eve of the Civil War.

They are just wonderful pieces of both anger and pride.

Pride at his own ability to stand up, resignation to the fate he will suffer, which he recognizes he will be martyred, but he knows it's for a good cause.

(melancholy piano music) - [Copeland] How, dear brother, could I die for a more noble cause?

Could I die, brother, in a manner and for a cause which would induce true and honest men more would honor me?

- In the letters home, John Anthony Copeland reaffirmed his religious devotion, his belief in abolitionism, and his respect for John Brown, even though he was going to face hanging for his participation in the attempt to free the slaves in Virginia.

- But he basically identifies with the Founding Fathers.

He cites Jefferson.

He identifies with the principles of the American Revolution and says, "I'm doing what Washington," you know?

"I'm dying for the right cause."

(stirring piano music) - [Copeland] It is not the mere act of having to meet death which I should regret, but that such an unjust institution should exist as the one that demands my life.

- He was executed on December 16th, so he had been in jail from October 18th or 19th until December 16th, and that was the execution.

- One of the things that's most devastating for his parents is that because they are free people of color, they cannot go to the state of Virginia to retrieve the body.

So they have to ask James Monroe, a professor at the college, if he would mind going down and trying to retrieve the body.

- It was risky for Monroe even to set foot in Virginia.

It was so risky that when he registered at his hotel, he had to put his home, and he put Russia instead of Oberlin.

Russia Township is where Oberlin is located.

He went to the medical school and persuaded the dean to release the body of Copeland, but the medical students refused and they threatened violence, and so Monroe went home empty-handed.

- Monroe gives, again, a terrifically moving speech at First Church on Christmas day of 1859.

- Memorializing Copeland and Leary, and there's a monument today in Oberlin to Copeland and Leary and Green.

- What we end up with is this little stone to commemorate them as a monument in Martin Luther King Park here in Oberlin.

There are no bodies.

- The first responses from many of the leaders of the anti-slavery community in Oberlin to the raid are denial.

"We had nothing to do with it.

These were not our people."

And that slowly, slowly shifts.

I think Copeland's letters help it and help community begin to embrace this hero of Harpers Ferry and the notion that violence may, in the end, be necessary.

- [Copeland] I'm only leaving this world filled with sorrow and woe to enter into one which there is but one lasting day of happiness and bliss.

(tender instrumental music) - [Narrator] John Copeland was executed in Charles Town, Virginia on December 16th, 1859.

On his way to the gallows, he reportedly said, "If I am dying for freedom, I could not die for a better cause.

I'd rather die than be a slave."

- These are foundational events that led to the country deciding that it is gonna take war to end this.

It's gonna take the shed of blood.

- [Narrator] More than 600,000 men died in the Civil War.

The Confederate States surrendered in April of 1865.

The 13th Amendment abolished slavery, freeing more than 4 million African Americans.

- After the Civil War, many of the town's leaders believed that having accomplished freedom, Black people should be able to do anything they wanted to.

Everything will become equal.

That's 1865.

That's wishful thinking.

By the time you get to the 1880s, 1890s and 1900s, the economic inequality of Black and white people in Oberlin has increased.

Oberlin loses its commitment to radical racial egalitarianism.

You can see that there are no Black people on the school board.

You can see that there's decreasing wealth among the Black population, and there's increasing residential segregation.

- Deed restrictions in Oberlin, Ohio.

(soft instrumental music) And so it went through a rough period of, you know, kind of falling to the whims of Jim Crow in some ways, even in the North.

- Many of the Black leaders of the community after the Civil War do have national possibilities.

O.S.B.

Wall becomes a police magistrate.

John Mercer Langston becomes the founding dean of Howard Law School.

The Henry Evans family also moves to Washington DC, and these are families that move into a Black elite in other places, leaving Oberlin without its longstanding Black leadership.

And without that longstanding Black leadership, there is no new generation coming up to take their places.

Oberlin leaders are no longer used to seeing the shops, the artisans, grocers, and restaurateurs who were there in the Antebellum era and the years immediately following the Civil War.

They're not there.

Oberlin is a thoroughly segregated town in the 1930s.

There's Black recreation and white recreation.

Where you used to have a Black person on the City Council for most years, after 1865, you come to a long period of time in which it's on again off again until you get to 1912, after which there is no person of color on the Oberlin City Council until 1954.

- You know, we see racism in Oberlin, but we turn a blind eye and we become mum to the fact where racism is occurring, but it's Oberlin.

And since it's Oberlin, it cannot happen here.

In reality, it does.

Yeah.

- One of the things that we do here in Oberlin is we look back on our glory days, the founding of the colony, the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, and we pat ourselves on the back and say, "We did the right thing and wasn't it grand?"

But we forget that that story didn't continue in a straight line afterwards.

And while we have continued to be a very progressive community in many ways, we struggle like all across this country with race relations, with separate Black and white churches.

Even though we do manage to do some things together, we are actually many communities within one community that is only what, 8 to 9,000 people.

- It's a place where we have gained so much, but it's a place where we need to further more opportunities for everyone.

(gentle instrumental music) - I think you can see a direct connection between where the citizens were then and where our community is today in regard to issues like the sanctuary movement.

So in the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, they were in essence providing sanctuary.

They were going out and rescuing somebody, bringing them into sanctuary, and getting them to a safe place where they could live out their life.

This community's commitment throughout the immigration crisis to say, "This will be a sanctuary city for immigrants that are looking to stay in this country and are at risk at of deportation.

While you are working that out, we will do everything we can to keep you safe."

- Right, we are a town that had this rescue.

We are a town that have this college that accepted all individuals, so we should rest on our laurels with that.

And it seems as though we are being stagnated, and so we just need to move a little bit further.

- We are aware of that and we are still in the struggle to find ways to bridge that gap, to deepen our relationships with one another.

We often tell ourselves, and probably others as well, that if we can figure out how to do it in Oberlin, then maybe we could teach others how to do it and other people could find that way.

So we're constantly experimenting, trying to figure that out.

I don't know that we've come up with any grand solutions, but we're still in the fight.

- [Narrator] Just as the rest of the country has struggled to maintain its stance on equality, so did the people of Oberlin and Wellington, but they still believe the principles behind a higher law will guide them in a fight for justice.

- You got to deal with the fact that sometimes you have to violate the laws of the land in order to be the saviors of tomorrow.

(warm instrumental music) (warm instrumental music continues) (warm instrumental music continues) (warm instrumental music continues) (bright uplifting music) (bright uplifting music continues) (bright uplifting music continues) (bright uplifting music continues) (bright uplifting music continues) (bright uplifting music continues) (bright uplifting music continues) (bright uplifting music continues) (bright uplifting music continues) (bright uplifting music continues) (warm instrumental music) (warm instrumental music continues) (warm instrumental music continues) (warm instrumental music continues) (gentle instrumental music) (warm uplifting music) (warm uplifting music continues) (warm uplifting music fades)

Preview: A Higher Law: The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue of 1858

Preview: Special | 30s | Discover an amazing story of abolitionism in Ohio and how it impacted the nation. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

PBS Western Reserve Specials is a local public television program presented by WNEO