Finding Your Roots

Children of Exile

Season 8 Episode 3 | 52m 20sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Retracing the ancestral journeys of David Chang and Raúl Esparza.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. retraces the ancestral journeys of David Chang and Raúl Esparza, whose families fled their homelands, leading them to find lost parts of themselves along the way.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Children of Exile

Season 8 Episode 3 | 52m 20sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. retraces the ancestral journeys of David Chang and Raúl Esparza, whose families fled their homelands, leading them to find lost parts of themselves along the way.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

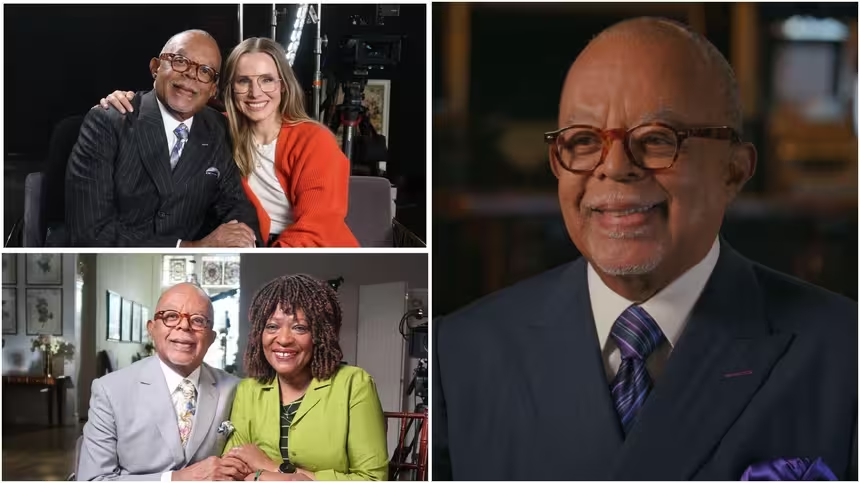

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGATES: I'm Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Welcome to "Finding Your Roots."

In this episode, we'll meet actor Raul Esparza and chef David Chang... Two men whose families fled their homelands, leaving them to wonder about all that was left behind... ESPARZA: At the time, it seemed to me like they left Cuba hundreds of years ago.

And only now do I realize how raw everything was.

CHANG: You know stuff happened.

And there was this unspoken rule that you just don't bring it up.

Ever.

GATES: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available.

Genealogists combed through paper trails stretching back hundreds of years, while DNA experts utilized the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets that have lain hidden for generations.

And we've compiled everything into a book of life, a record of all of our discoveries... CHANG: What is happening, man?

GATES: And a window into the hidden past... ESPARZA: That's crazy, man.

The weight of that much history is like... GATES: What does that journey, from them to you, mean to you?

CHANG: It puts a lot of things into perspective that I thought I knew about, but now I really didn't know anything about at all.

GATES: David and Raul are the children of exiles.

They've spent their entire lives wondering about places they've never seen.

In this episode, they're going to travel to those places, retracing the journeys their ancestors took, and finding lost parts of themselves along the way.

(theme music plays) ♪ ♪ GATES: Raul Esparza has been lighting up Broadway, and Hollywood, for more than two decades... Moving between wry musicals, and dark dramas, he's shown immense versatility and a seemingly bottomless well of talent.

But for someone who has embodied so many intense characters, Raul himself is surprisingly easy-going.

In person, he's soft-spoken, self-effacing, and eager to credit his family for his success... Learning their story, I understood why.

Raul grew up in a suburb of Miami, surrounded by parents and grandparents who'd fled Castro's Cuba and who were working hard just to make ends meet.

Even so, they encouraged Raul to follow his own passions.

ESPARZA: This is an interesting thing.

For the longest time, I said "I'm going to be a lawyer."

GATES: Mmm-hmmm.

ESPARZA: And all the way into college I thought that's what I'm going to do: be a lawyer.

GATES: Right.

ESPARZA: But as I got older and I got... Clearly was doing well with the acting, for some reason my parents encouraged me.

Which, you never hear that story.

And they said, "you should be... Do the thing you're good at.

Life's too short."

GATES: Hmm.

How do you explain that?

ESPARZA: I think it's because they're exiles, and I think it's because they lost everything they had, and they were like, "there's no guarantees, so why don't you just do the thing you love."

GATES: Raul's parents had an admirable attitude, but their support would be put to a stern test.

In 1999, when Raul was almost 30, and still barely making a living as an actor, he was cast as "Che" in a national touring production of the hit musical "Evita".

It was a plum role, but his character was based on Che Guevara, a leader of the Cuban revolution and a reviled figure in Raul's family.

Okay.

I want you to do me a favor.

Ring, your mother answers.

"Mom, get dad on the other line.

Guess what I've been cast to play?"

ESPARZA: Yeah.

I remember my mom said, "over my dead body."

And my grandfather said, huh?

What do you mean?

He's in a, you're in a, you're in a musical?"

I was like, "yeah."

"Che in a musical?"

I'm like, "yeah."

He's like, "hmmmm.

He didn't sing and dance."

Like, you know?

He's like, "uh, in a musical?"

I said, "yeah, it's a musical about the life of Eva Peron."

He's like, "They didn't know each other."

Everybody in the family is like, "I don't think so."

GATES: Raul, of course, took the part, and never looked back.

Not surprisingly, his family quickly forgave him the decision, and he's remained intensely loyal to them, grateful for the home that they created far from the place where they were born.

ESPARZA: You know, I think one of the reasons I'm an actor is because of the stories that they always told me.

Cubans tell so many stories that I think the idea of telling stories and sharing stories is kind of second nature to me.

My family's also kept me really grounded.

GATES: Mmm-hmm.

ESPARZA: I feel appreciated, I feel special, but I don't feel like anything anybody has to bow to and it's really good to keep things in perspective.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ESPARZA: I will say one of the biggest moments I had was on this musical, on "Company", which was a very big success for me.

And the day that my name was on the marquee at the Barrymore Theatre.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ESPARZA: I saw my name up there: "Raul Esparza in Stephen Sondheim's 'Company'."

GATES: Mmm.

ESPARZA: And I remember telling Steve Sondheim, like, "Steve, there's my name over the title of a show of yours.

I mean, it's a major revival.

I'm in the 'New York Times'."

He goes, "yeah, don't get too excited."

But I see the name and I'm like, "there it is."

And what I flashed on was my grandfather's name, my father's name, my great-grandfather's name.

You know?

It's like, "that's a, that's a Cuban name up there!"

GATES: Yeah.

My second guest is superstar chef David Chang.

Since 2004, when he opened his first restaurant, a noodle bar on Manhattan's lower east side, David has built a culinary empire by relentlessly mixing tradition and experimentation...

It's an approach that he traces back to his childhood home...

Growing up in Virginia, David vividly recalls that his mother, who had fled North Korea as a child, did not cook like the other mothers in town.

CHANG: I remember pretty early on there was a distinct difference between white people food and the food that my mom would make.

GATES: Right.

CHANG: And this is a story that I think many immigrant kids can relate to, is when you first bring someone over that isn't of your sort of ethnicity, and they eat the food that they've never had before, that you think is normal, definitely not normal to them.

GATES: No, right.

CHANG: So my brothers and I were like, "We only want to eat, you know, white people food."

GATES: Yeah.

And what'd your mother say?

"well, go next door."

CHANG: Yeah.

GATES: You know because... CHANG: No.

She tried her best to, to, to make it for us, right?

And, uh, she's an amazing cook, and, and it was what she thought a white family would want to eat, and that's sort of what we ate, is like "based on a true story."

GATES: Uh-huh.

CHANG: So, it was this Korean American mix of things.

Which, quite frankly, had a lasting impact.

I think it's why I am who I am today, at least in terms of what I explore, cuisine-wise.

GATES: Yeah.

"I want a hamburger and french fries!"

CHANG: Yeah.

GATES: While David may have inherited his cooking skills from his mother, his father was determined that he suppress those skills... And his father was an authority on the subject.

During David's childhood, his father owned and managed a series of restaurants in Washington, DC, and he most certainly did not want his son to follow in his footsteps.

Instead, his hopes for David were focused on something very different: the sport of golf.

CHANG: I had a complicated relationship with my dad.

He put a lot of pressure on me.

He just wanted me to be a professional golfer.

That was it.

That was his only dream.

GATES: What, where did that fantasy come from?

CHANG: I have zero idea.

It was the, of all the sports, uh, and that's what he wanted.

It had more to do with golf, everything to do with golf, and nothing to do with restaurants.

GATES: Given his father's feelings, David's path to success wasn't a smooth one.

He was actually a talented junior golfer, but he'd quit by the time he was 14.

After college, he quit a fledgling career in business as well.

Then he insisted on going to culinary school, against his father's wishes, and ended up with a job at New York's prestigious Mercer Kitchen.

Again, his ambitions began to waver, but this time he held on.

CHANG: I remember the first sort of six months of going to school and working at the Mercer Kitchen and then interning around various other places, that, this is not for me.

This is not for me.

But I had, you know, made such a big stink about this is what I was going to do, that it was pride that kept me in it.

GATES: Yeah.

You couldn't tell your father.

CHANG: Yeah.

GATES: You said, "got those golf clubs, dad?"

CHANG: Yeah.

And, you know, I think that's probably the only talent that I have, is that I'm just stubborn enough to keep on doing something.

GATES: God, I wonder where you got that from?

My two guests both grew up in families struggling to plant roots in exile.

This poses a unique challenge to genealogists... An exile is not simply an immigrant.

They're people who, for political reasons, cannot return to their native lands, this means that they live cut off from their ancestry, unable to access their own family history.

It was time to see if we could restore what had been lost.

We started with Raul Esparza.

Both of his parents came to the United States from Cuba in the 1960s, as did their parents.

None of them ever returned, but Raul has long noted that the two sides of his family have very different attitudes toward the island they left behind... ESPARZA: On my mom's side, Cuba, that was like paradise lost, the most beautiful place anyone had ever been.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ESPARZA: Everybody in Cuba used to be a prince, I guess.

So that's that side of the story.

Cuba was this, like, palace of beauty.

And it was quite, um... My mom would talk about the dances that they would go to and how much fun that was, and, like, the, uh, experience of growing up in what seemed like a fairy tale.

GATES: Right.

ESPARZA: On my dad's side, they didn't really talk about it very much.

I, I didn't know why until many years later.

Many, many years later.

GATES: Right.

ESPARZA: And my dad would say, "yeah, I didn't, I didn't, I don't think we need to talk about that place.

It was fine."

GATES: Raul's father's reticence was the byproduct of some very complex history.

In February of 1959, Fidel Castro became the Prime Minister of Cuba, after leading a revolution against Fulgencio Batista, a military dictator who'd been supported by the United States.

It was a time of great hope for many on the island.

But the new government would soon embrace some Marxist-Leninist philosophy, and Raul's family was deeply tied to that government.

Indeed, by 1966, Raul's grandfather was a high-level official in Cuba's Ministry of Sugar, a position that complicated the fact that he and his wife were growing increasingly disaffected by conditions within the country that he was helping to lead.

Things reached a head, according to the family, when their two sons were expelled from the University of Havana.

ESPARZA: My dad tells the story that because he wouldn't join the party, um, he was, he was expelled, which is why my grandmother said she felt like... GATES: "Time to go."

ESPARZA: "We're done here."

GATES: Yeah.

ESPARZA: "The boys have no future."

The disappointment was that they really did think, new government, new hope, new chance, the country could be better than it's ever been.

GATES: Right.

ESPARZA: And the disillusion was, like, that it got more and more repressive.

GATES: There are no firm statistics, but scholars estimate that after coming to power the Castro government executed thousands of Cubans, many more were imprisoned, while personal freedoms were curbed, and escape from the island nation became increasingly difficult.

Nevertheless, Raul's grandparents were determined to leave, his grandmother perhaps most of all, ESPARZA: My grandmother told me about struggling to get out more than once, and having to turn back... GATES: Ahh, okay.

ESPARZA: On her own, with the boys.

And making mistakes where they could get caught.

Bumping into militia members, bumping into, you know, ending up in mangrove swamps, crawling through that swamp to escape.

GATES: Right.

ESPARZA: They just couldn't find the right time.

GATES: Right.

ESPARZA: And she was doing it, my, she had told my grandfather, "I will do this without you."

GATES: Oh, wow.

ESPARZA: And that's the part I can't even imagine.

GATES: Yeah.

ESPARZA: My grandmother was a really sweet, fun woman.

You'd look at her and be like, "what'd you do?"

GATES: In February of 1966, Raul's grandmother took the ultimate risk.

She left Cuba in an open-air boat with her two sons, and a handful of other desperate women and men.

For two days, they crossed what was known as "machine gun alley", the deadly waters that separate Cuba and Florida, patrolled by Cuban gunboats and hungry sharks.

Remarkably, a photo of their arrival survives, taken from a helicopter belonging to the United States Coast Guard.

ESPARZA: How extraordinary.

You know, the thing about the Cuban stories is that, like, everybody feels like, "well, that story is the exceptional one."

But then you hear thousands of that story.

GATES: But this is pretty exceptional.

ESPARZA: It is pretty exceptional, yes.

I'm not saying that.

It's just a, it's an entire, it's generations of, of, of these kinds of stories about coming to America.

GATES: Raul's grandmother's escape was all the more incredible because she was on her own, without her husband.

At the time, he was in London as part of a Cuban delegation attending a United Nations meeting on sugar standards, which placed him in a frightening position.

What do you think it was like for your grandfather?

ESPARZA: I can tell you that because I know he's told me that it was, that he went, that he just went white.

That he went completely into shock about it.

GATES: I bet.

ESPARZA: And then, and then fear of realizing that "my op, my options are get out or you're, or you're in trouble."

GATES: Raul's grandfather would now make a daring escape of his own... Defecting to the United States via Spain, likely with assistance of one of the many anti-Castro organizations that were supported by the CIA.

Though his movements are not documented, he would tell his story to a subcommittee of the United States Congress investigating the growing crisis of Cuba's refugees.

ESPARZA: "The call informing me of the arrival of my family in the United States came precisely while I was meeting with the other delegates.

These were watching me attentively as if they wanted to guess what I was being told from the other end of the line.

Therefore, I had to take resources from my scarce acting abilities and pretend that this was an official call from Cuba.

I chose to tell them that the Cuban government was charging me with some additional business that would keep me in Madrid for a few days.

The Spanish authorities gave me all kinds of assistance, which later included personal protection.

When the Ministry of Sugar learned of my disappearance the government instructed the Cuban embassies in Madrid and London to hunt me down and send me back to Havana."

GATES: Wow.

ESPARZA: What's so powerful about this is that i, I know this story but you don't know the, I have never read this so I don't know the specific, the details coming from my own grandfather's mouth.

You know?

GATES: Yeah.

Yeah.

Official testimony.

ESPARZA: Yeah, official, like, because it's such a complicated story you're like, "well, that sounds like somebody's making something up."

And they didn't make anything up.

GATES: No, they didn't make anything up.

Finally reunited, Raul's father's family settled in Florida and began to rebuild their lives.

His grandfather found work in the local sugar industry, and though he never lost affection for his native land, ultimately he came to love his new home on its own terms, becoming an American citizen when he was 56 years old.

ESPARZA: "At West Palm Beach, Florida on July 9, 1976, Raul Esparza was admitted as a citizen of the United States of America."

GATES: Have you ever seen that?

ESPARZA: No.

GATES: How does that make you feel?

ESPARZA: Pretty great.

GATES: You were six years old at the time.

Any recollection of that event?

ESPARZA: No.

No, I don't remember this event.

I remember my mom's mom becoming a citizen, but it was much, much later in her life.

GATES: What do you think your grandfather was feeling at that moment?

ESPARZA: Conflicted.

But also secure.

My grandparents on my dad's side really loved this country.

GATES: Yeah.

ESPARZA: They really felt very proud and safe here.

GATES: As it turns out, Raul's grandparents weren't the first in his father's family to make the journey to America.

Moving back two generations, we came to his great-great-grandmother, Rosalia Gonzalez y Arencibia.

On July 2, 1900, she arrived in Boston from Havana, not as a refugee, but as a professional.

ESPARZA: "Destination, Cambridge.

Occupation, teaching."

So she was a teacher in Cambridge.

Did she come to teach?

GATES: Well, let's find out.

Could you please turn the page?

Raul, the article in front of you was published on May 4, 1900 about two months prior to Rosalia's arrival in Cambridge.

ESPARZA: I see.

"Five government transports sailing from different ports in Cuba will bring to Boston 1,450 Cuban teachers selected from all parts of the island, rural as well as urban.

These selected teachers are to attend a summer school at Harvard University."

GATES: Your great-great- grandmother was 46 years old, married, and a mother to seven children when she did all this.

What's it like to see that?

ESPARZA: Exciting.

It's making me imagine a whole life, uh, that I wasn't even aware was happening, um, back then.

It's really, really cool.

GATES: Rosalía came to Harvard as part of an effort to export the American educational system to Cuba following its liberation from Spain in the Spanish-American war.

After six weeks, she returned home, and resumed her career as a teacher.

She also began publishing articles in a variety of magazines, often using a pseudonym, a common practice for female writers at the time.

Did you have any idea... ESPARZA: Nope.

GATES: That you had an ancestor who's a writer?

ESPARZA: No.

I mean, no.

She sounds fantastic.

GATES: Yeah.

ESPARZA: And, uh, to think of a mother, a woman at this time, now it would be a big deal.

Then it's exponentially so.

GATES: Oh my god, yeah.

ESPARZA: That's really kind of amazing.

GATES: We had one more surprise for Raul.

In Havana, we uncovered the baptismal record for Rosalia's father, Manuel de Jesus Gonzalez Cabrera.

This is the oldest document that we could find for Raul's ancestors in Cuba, and it illuminates his deep roots in a place he's never been.

ESPARZA: That's crazy, man.

The weight of that much history is like... GATES: Oh, yeah.

ESPARZA: You know what I mean?

How amazing.

GATES: And that also tells us the names of Manuel's parents.

ESPARZA: Antonio Gonzalez and Juana Josepha Cabrera.

GATES: Yes.

Antonio and Juana are your fourth great-grandparents.

Great-great-great- great-grandparents.

ESPARZA: That's tremendously interesting.

GATES: Did you have any idea that you had roots on the island that went back that far?

ESPARZA: No.

No, I always wondered, like, how connected were we really to Cuba.

Quite.

GATES: Connected.

Conexión.

ESPARZA: Yeah.

GATES: What are you feeling?

ESPARZA: I feel, I'm very, I'm moved, and I'm also very, very proud.

You just keep thinking "I'm part of that.

Look what they did.

Wow.

Look what I come from.

Look what they accomplished?"

That's, um, feels very comforting.

GATES: Like Raul, David Chang grew up wondering about a homeland that he hasn't ever seen... His parents were both born in what is now North Korea, and both left as young people amidst the chaos of the Korean War, never to return.

But while Raul grew up hearing stories about Cuba, David's family rarely spoke about their lives in Korea.

David knows that his father and mother came from very different backgrounds, but that's where his understanding ends.

CHANG: I divide it in, my mom's side of well-to-do, you know, I know my mom grew up in, like, in a castle, right?

GATES: Uh-huh.

CHANG: I saw a photo of it.

I was like, "what?"

And my dad's side is basically just hustlers.

That's how i, that's how I divided it.

And I don't know anything other than that.

GATES: Why didn't you ever ask?

CHANG: I don't know.

I think it was a sense of sorrow.

I mean, you know stuff happened.

GATES: Right.

CHANG: And if it came out great, we wouldn't be in this country.

GATES: Yeah.

CHANG: And I think that was sort of, like, deeply rooted in me as to don't ask these questions.

GATES: As we set out to trace David's ancestry, we soon discovered that his parents were not actually the first members of his family to cross the globe in search of a better life.

That title belongs to David's maternal great-grandfather, a man named Woo Sang Yong.

Sang Yong was born in the late 1800s in what is now North Korea.

In 1910, when he was roughly 16 years old, Japan annexed Korea, and its people became second-class subjects of the Japanese empire.

It was a dark time in Korean history, but Sang Yong didn't have to endure it for long.

In 1920, he was sent to the United States to study theology, chosen, according to a newspaper article, by the methodist church for his quote-unquote "exceptional future prospects".

CHANG: I can't even stress how crazy this is.

GATES: 101 years ago, that article was published.

CHANG: That's so wild.

GATES: Think about how rare that opportunity was.

I mean, this is the beginning of the jazz age, man.

This was a century ago.

He must've been extraordinary to have been chosen for this program.

CHANG: I don't even... GATES: And it had to be a little bit like going to mars, I mean.

CHANG: I don't have words.

I mean, I have goosebumps.

GATES: Sang Yong came to America leaving behind a wife and a young son.

We don't know how long he intended to stay, but it's highly unlikely that anyone imagined the future that lay ahead.

In 1925, a full five years after his arrival, he received a certificate in theology from Southern Methodist University in Dallas, but he wasn't ready to go home.

That same year, he was admitted to the Yale Divinity School!

We found his application which describes, in his own words, his amazing journey... CHANG: Wow.

This is so crazy.

Oh my goodness.

"I spent many years studying the classics and poetry in Korea.

Then I went to high school and from there to normal school where I stayed two years and would have stayed longer had the school not closed because of lack of funds.

My work in college has been the prescribed work for a degree in theology."

Wow.

This is all news to me, and I'm trying to imagine his life in America as a student with a wife and a young son back in Korea, spending all this time in America.

GATES: Mmm.

Oh, it had to be lonely and culture shock and alienation.

And nobody talked about it?

CHANG: No.

No.

No.

That's a lot to take in.

GATES: This story was about to make a surprising turn.

Sang Yong arrived at Yale in the fall of 1925, but soon developed a serious respiratory condition.

Doctors recommended that he return to Korea, but he didn't follow their advice.

Instead, he connected with two other expatriate Koreans and essentially became an entrepreneur, opening a series of Asian-themed gardening businesses throughout the United States.

CHANG: "Mr. S.Y.

Woo was told he would have to have a delicate and expensive nose operation.

To raise the money, they decided to open a small gift shop during the Christmas holiday season.

Then things began to happen in bunches.

The Depression struck and demand for the luxury gardens fell.

Woo sold his store and opened a greenhouse in Cleveland..." In Cleveland?

What the hell is happening?

"In 1931, the JL Hudson company of Detroit invited Woo to open a Chinese garden department in their store.

Woo accepted, and soon the family was together again."

What?

So, he's, he's just hustling.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CHANG: What is shocking is I didn't think the entrepreneurial thing came from my mom's side.

GATES: Right.

CHANG: I thought it was all my dad's side, all of it.

GATES: Uh-huh.

CHANG: But I'm wrong.

I'm happily wrong.

GATES: Unfortunately, Sang Yong's travels would reach a tragic end.

After World War II, he found himself back in Korea, where, in the wake of Japan's defeat, his homeland had been partitioned into a communist north backed by the Soviet Union, and a capitalist south, allied with the United States.

There was a great demand in the south for Koreans who spoke english, and, ever resourceful, Sang Yong obtained work as a guide for American soldiers and civilians.

That decision would lead to his death.

CHANG: "Coming back from a boar hunt, the jeep in which he was riding with Americans was sideswiped by a Korean truck.

Mr.

Woo was the only one seriously injured.

He was unconscious, of course, and lost much blood before his American hunting companions were able to secure an ambulance and take him to an American hospital.

While we sat and waited for the verdict, the American doctors gave him first aid, set his arm and then, surprisingly, said they could do no more.

The rules, they said, were first that they were not to treat Koreans."

They couldn't do any more because he was Korean?

GATES: Yeah.

Get this: according to the article, the doctors were under combat regulations and could've done more to save him, but didn't, because the doctors didn't want to get into trouble.

Now, what kind of doctor is not going to save another human being?

CHANG: That's unfortunate.

GATES: Well, it's, it's disgusting.

CHANG: You know, I just, I didn't even contemplate or imagine his death.

GATES: Uh-huh.

CHANG: That it could be like this.

I mean, no surprise, i, I barely knew his life.

Why would I know his death?

GATES: Yeah, of course, yeah.

But you never would've, you couldn't have guessed.

CHANG: Well, he lived a full life, for sure.

GATES: He lived a full life.

He did indeed.

CHANG: Unbelievable.

GATES: There was one final beat to this story.

As we combed through the records that Sang Yong left behind, we noticed that in his application to Yale, he named his father, which ultimately allowed us to identify his father, who was likely born in the mid-1800s.

Giving David the chance to glimpse two more rungs on his family tree!

Have you ever heard their names before, or heard anything about them?

CHANG: I never even thought of their existence.

GATES: Yeah.

Well, your second great-grandfather, your great-great-grandfather, was a farmer and a merchant who supported his son's family while his son was studying for ten years in the United States of America.

And you had no idea.

CHANG: I was, i, I mean, I was, like, pretty sure there was some farmer in my family.

GATES: Right.

CHANG: But I didn't know how far back it was going to go.

You know?

This is amazing.

GATES: Mmm.

CHANG: It makes me proud, and that's a word I never really use to describe my family.

GATES: Why not?

CHANG: I just never had that connection.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CHANG: I think a lot of it was my own sort of projection of maybe being Korean in America, how would I know that there was this rich history that even spent a lot of time in America?

GATES: Right.

What does that journey, from them to you, mean to you?

CHANG: I think it means that I got to do better, you know?

Whatever it is I do that, a lot of things by chance and just events and hardships and amazing things have all, like, all this life happened for me to have this opportunities, these opportunities that I have, and just my, my, my overriding sense of who I am tells me that i, i, more than ever, that I need to just not squander these opportunities.

GATES: We had already surprised Raul Esparza by tracing his paternal roots in Cuba back two centuries.

Now, we had a very different kind of surprise to share.

Following his mother's father's line, we found ourselves far from Cuba, in the Catalonian region of Spain, where Raul's ancestors were doing something quite unexpected... ESPARZA: "Luis Garcia de Pou, occupation, commerce.

Francisca de Pou Agusti, occupation, owner."

GATES: Raul, this tells us that your second great-grandmother, Francisca, your great-grandfather Luis, and your great-granduncles Julio and Emilio, were all engaged in commerce, quote-unquote.

ESPARZA: Commerce.

Yeah.

GATES: Any idea what type of commerce?

ESPARZA: No.

GATES: Well, let's find out.

ESPARZA: Okay.

GATES: Would you please turn the page?

Would you please read the translated section?

ESPARZA: "In 1884, Luis Garcia de Crespi, first chief of the Figueres railroad station, opened a paper bag factory.

He came from Valencia and like a good entrepreneur started different businesses before realizing that the workshop had a future.

He married Francisca de Pou, which is why he named his new business Garcia de Pou."

GATES: That is your great-great-grandfather.

ESPARZA: Great-great-grandfather?

GATES: Yes.

And he founded your family's company.

You can see his photo right there on the left.

ESPARZA: How cool.

Wow.

GATES: The story of this branch of Raul's family is set down in a wealth of corporate documents, newspaper accounts, and even a book on Catalonian industry...

It seems that over the years, Luis and his wife Francisca ran a cement company and a paper bag factory, a factory that began as a workshop in their own home.

ESPARZA: Paper bags?

GATES: Paper bags.

Catalonia was an important paper-making area because of two main factors: large demand spurred by high population and access to natural resources like clean water.

So your ancestors must have seen an opportunity for themselves and they went for it.

ESPARZA: I guess you don't even think about... You're talking about paper bags and I'm going I guess I always thought they always existed.

Paper bags just are in the world.

GATES: Raul's ancestors may have chosen to take their chances on rather mundane products, but the gamble paid off.

They soon had at least 60 employees!

Unfortunately, in July of 1900, Luis died unexpectedly, leaving Francisca as one of a tiny minority of women running companies in Spain at that time...

It was a daunting challenge.

She would have been a 42 year old widow with three sons.

ESPARZA: Yeah.

GATES: It couldn't have been easy for her.

I mean, think about it: she was running at least two businesses simultaneously at a time when women were still largely relegated to jobs in domestic service and retail, if they were allowed out of the house... ESPARZA: Yeah.

GATES: At all.

She had to be one tough lady.

ESPARZA: Yeah.

GATES: Francisca would prove to be both tough, and savvy.

Under her watch, the paper company became wholesalers, selling wrapping for food products, and continued to thrive...

But when it came time for Francisca to hand over the business to her eldest son, Raul's great-grandfather, she was less successful.

His interests, it seems, lay elsewhere.

As evidenced by the 1906 census for Spain.

ESPARZA: "Luis Garcia de Pou, 25, single, occupation: bohemian."

GATES: The census taker described your great-grandfather's occupation as that of a bohemian.

ESPARZA: A bohemian.

GATES: Not as a cement maker.

ESPARZA: No, not a cement or paper bag maker, unless he was wearing paper bags.

GATES: That's a good one.

What do you make of that?

ESPARZA: I'm surprised by it because bohemio is definitely, uh... That is a phrase they've used about me.

My grandmother has said to me, "muy bohemio," which is... GATES: Yeah, yeah.

It doesn't sound like it is, um, a term of praise or admiration in 1906.

ESPARZA: No.

He's, uh, not a realist.

Uh, "artistic temperament" is what bohemio always makes me think of.

Or a vagabond.

GATES: Raul was curious as to how his "bohemian" ancestor spent his time.

According to Catalonian newspapers from the era, it seems he ran an organization for young artists.

We're not exactly sure what the organization did... ESPARZA: I wonder.

GATES: But its goal, seemingly, was to create and encourage as many artists as possible.

What in the world do you make of that?

And could you have any idea that on your family tree was an ancestor like this?

ESPARZA: No, not at all.

Not at all.

GATES: Huh.

ESPARZA: And I've always wondered, like, where did I get this interest from, or this, uh, attachment to, to the arts that I have.

GATES: It was in your blood and you didn't even know.

ESPARZA: I had no idea.

GATES: You've been informed by things your ancestors have done osmotically, though you didn't know.

ESPARZA: It's so, but it, what it feels like is delightful.

Um, I mean, I have no idea what the thing is itself, but it's delightful to, um, imagine how important this must have felt to, to them, I guess, to make this organization at the time, and delightful to make a small connection that I've always wondered about for myself.

GATES: Perhaps unsurprisingly, Raul's great-grandfather didn't stay a bohemian forever.

He eventually married, had a child, and took over the company his parents had founded.

But even so: he remained a restless soul.

Sometime around 1916, Louis left the paper business behind yet again, and emigrated to Cuba with his family, where his son, Raul's grandfather, would become a bookkeeper, and eventually flee Cuba for the United States, bringing the story of this line of Raul's ancestry up to his own birth.

But there was still a question in front of us: what happened to the family company back in Spain?

The answer surprised us both.

ESPARZA: "Garcia de Pou, with headquarters and factory in Vilasacra, sells all kinds of single-use paper products like napkins, coasters and paper towels to restoration companies, hotels, hospitals, and airplane companies."

They did just fine.

GATES: The company is still in operation.

ESPARZA: That's crazy.

GATES: And not only that, it is still owned and operated by your family.

Look at it on the left.

ESPARZA: It's gigantic.

GATES: That's its headquarters.

ESPARZA: Maybe I should go into paper work.

Look at that.

GATES: Your family's company currently has 400 employees... ESPARZA: That's amazing.

GATES: More than 25,000 clients, and exports its paper products to over 50 countries.

ESPARZA: This is crazy.

GATES: We had one more detail to share with Raul.

When we looked into his great-great-grandmother Francisca's roots, we discovered that she had been born in the tiny town of Navata, Spain, where, incredibly, Raul's family can be traced back 14 generations.

ESPARZA: It's like looking through a fog at the past all of a sudden.

Look at that.

GATES: Yeah.

It's pretty cool.

ESPARZA: That is really wonderful.

GATES: They have lived in Navata at least since 1635.

ESPARZA: Yeah.

GATES: What's it like to know your, that your roots go back so deeply in this one place?

ESPARZA: I think it's marvelous.

GATES: They didn't move.

ESPARZA: They didn't move.

Stubborn Spaniards.

But, um, how stable and extraordinarily consistent.

My god.

And that's just, like, I was already kind of blown away when we were talking 19th century.

Now I'm looking at... GATES: 17th century.

ESPARZA: 17th century and it just feels like, "what?"

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ESPARZA: It's, uh, spectacular to see such an incredibly strong connection to one place.

GATES: Right.

ESPARZA: Because the Cuba foundation is really fragile.

You know?

This is centuries and centuries and centuries... GATES: Right.

ESPARZA: Of life, in a place.

Because Cuba's the place they left.

GATES: Yeah.

ESPARZA: How magnificent.

GATES: We had already explored how David Chang's maternal ancestors left Korea for the uncertainty of America.

Now, turning to his father's roots, we found ourselves retracing that same journey, but from a very different perspective.

David's father, Chang Jin Pil, came to the United States in the early 1960s with no safety net, and spent years working menial jobs in restaurants.

Though he would ultimately own several businesses, none brought him lasting prosperity, or peace, and David is still struggling to understand him.

CHANG: You know, what's funny is my brothers were telling me "your dad gets better when you get older."

GATES: Uh-huh.

CHANG: When you turn a certain age, and I was like, "whatever."

GATES: Uh-huh.

CHANG: But it dawned on me: he didn't have any way of communicating with some kids growing up in America, with American values.

And whatever his life was, there was no way for him to relate.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CHANG: And when I think of my dad, I say it lovingly, and it's how I phrase, like, I think about a lot of his side of the family, but more so my dad, I just think about that guy hustling, always, to find a way to make something work.

GATES: Right.

CHANG: Yeah.

Finding a way against all odds.

GATES: David's father rarely spoke about his personal life other than to say that his childhood in Korea was a hard one, and all evidence suggests he was right... Jin Pil was born in 1942 and came of age during the Korean War, a cataclysm that caused roughly three million casualties, and made refugees of at least another million more.

David gleaned some insight into just how difficult these years were by observing his paternal grandmother, who followed her son to the United States.

She was strict, religious, and extraordinarily frugal.

As children will do, David and his siblings mocked her for being so different.

But as he matured, David realized that her habits were the residue of great suffering... CHANG: I feel remorseful that we made so much fun of her, you know?

She had no idea what we were saying.

She only spoke Korean, and she would always wear the Korean hanbok, the traditional dress.

And she was so tiny.

And she just was so hardcore.

And I remember when we would make rice, and if there was any leftover rice, she would make sure that every grain of rice was dried out on the, on the, on the deck outside.

GATES: Huh.

CHANG: All the time.

And my brother and I were just like, "what the hell is she doing?"

GATES: Right.

CHANG: And she would do that with a lot of food, but I just remember the rice.

And she would never let anything be thrown away.

Ever.

And she would then use that rice to put something in her barley tea, you know?

GATES: Uh-huh.

CHANG: It was just so weird to me then.

It's still a little bit weird to me now.

And how opposite it was from my, my mom's mom, who has the more sort of like loving, maternal instinct type of thing.

GATES: Right.

Uh-huh.

CHANG: And that was much more easily accepted and understood by us, the siblings.

Whereas my mom, my dad's mom, I think, was trying to show love by just teaching us how to survive.

GATES: Uh-huh.

CHANG: That's how I feel.

GATES: Well, survival was in, the need to survive, the desperate need to survive was in her DNA.

CHANG: Yes.

GATES: Given the barriers between them, it's not surprising that David knew almost nothing about his father's deeper roots, and due to the challenges of conducting research in North Korea, we expected that we would be able to add little to his knowledge.

But we were wrong.

David has distant relatives who have preserved the family's jokbo, a written genealogy that allowed us to tie David to one of Korea's ancient clans, founded by a man named Chang Jeong Pil over 1,000 years ago... CHANG: This is, like, unbelievable.

It's funny, the, the biggest thing that I'm thinking of is that my dad's middle name is Pil.

GATES: Uh-huh.

CHANG: And to see that it went back many, many years.

GATES: It goes back to your 34th great-grandfather.

We estimate that Chang Jeong-Pil is your 34th great-grandfather.

CHANG: It's just something my dad never spoke about, ever.

GATES: Isn't it cool that these clan genealogies exist?

CHANG: It's wild to me.

I think about this a lot, it's something I always grew up jealous of, I think, of, of my, my, my, my friends that have European ancestry, and they can go way back, way back, like, "oh, I..." GATES: And a coat of arms?

CHANG: Yeah.

GATES: Yeah.

CHANG: And it's like, oh, that's, I'll never know what that's like.

And here it is.

GATES: We cannot verify the accuracy of every rung of the tree in this jokbo, but according to scholars, there is a widespread consensus that David's clan affiliation ties him to a very illustrious ancestor: a legendary mariner and warrior named Jang Bogo.

Jang Bogo became a national hero following his death in the year 846...

Giving David a new appreciation for all the history that his father left behind.

CHANG: It's like, I almost don't want to believe that this is true because...

I just grew up thinking there's no way this lineage can, like... GATES: Jang Bogo is still celebrated in South Korea today.

He has been featured in both a South Korean television series and a film, and the South Korean navy named a whole class of attack submarines after this bad brother.

CHANG: Wow.

GATES: Does learning about this make you think any differently about your father?

CHANG: I guess it adds to the complexity.

GATES: Right.

CHANG: I spent so much time trying to think about him acclimating to America, I never, ever once really thought about his life, pre, you know, immigrating.

GATES: Uh-huh.

CHANG: I mean, it's amazing.

It puts a lot of things into perspective that I thought I knew about, but now I really didn't know anything about at all.

GATES: The paper trail had now run out for both David and Raul.

CHANG: Wow.

GATES: It was time to show them their full family trees.

CHANG: This is amazing.

GATES: Mapping the deep roots that had vanished in exile... ESPARZA: How extraordinary!

GATES: These stories will never be lost, these names will never be lost.

CHANG: I've always wanted this, always.

GATES: Seeing their ancestry traced back centuries, in places both familiar and unexpected, compelled both men to rethink their own identities... CHANG: You know, I grew up with this notion that there's nothing special about my family, you know?

And I think a lot of that is, again, having this immigrant mentality of being marginalized, or what you think is special is not really special.

But, I mean, a lot happened for me to be here.

GATES: Right.

CHANG: And I think that changes my sort of understanding, uh, so I got to, I got to do some more meditating on what that means to me.

ESPARZA: Right now, I feel slightly off-balance.

I can confirm that who I am is in my DNA, so to speak, and my interests and how I feel and think.

That feels very solid.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ESPARZA: But what it also does is make me feel like I don't know myself at all.

There's more to find out, more that I'm made up of.

GATES: That's the end of our journey with Raul Esparza and David Chang.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests, on another episode of "Finding Your Roots".

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S8 Ep3 | 30s | GUESTS: David Chang & Raúl Esparza (30s)

David Chang Discusses Things His Family Never Talks About

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep3 | 1m 25s | David Chang describes being aware of his parents’ vastly different economic backgrounds. (1m 25s)

David Chang Imagines His Great-Grandfather’s Life in America

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep3 | 1m 4s | David Chang reacts to reading his great-grandfather's application to Yale Divinity School. (1m 4s)

David Chang Shares A Story Relatable to Many Immigrant Kids

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep3 | 1m 6s | David Chang discusses his mother’s culinary influence on him. (1m 6s)

Destination: Cambridge. Occupation: Teaching

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep3 | 1m 3s | Raul learns about his maternal great-grandmother's stint at Harvard. (1m 3s)

Raul Esparza on His Father's Disillusionment with Castro

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep3 | 36s | Raul Esparza describes his father’s and uncle’s disillusionment with Cuba's Castro regime. (36s)

Raúl Esparza Reads His Grandfather’s Congressional Testimony

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep3 | 1m 30s | Raúl Esparza Reads His Grandfather’s Congressional Testimony (1m 30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: